Linux Kernel Management

Understanding how Linux kernels load, and how to resolve issues if they don't

This topic is fairly new to me and always seemed like a bit of a beast to tackle. Something about the term “kernel panic” just makes me shy away from looking into exact causes but now that my knowledge of controlling a Linux machine for both Debian and RPM has improved, I think it’s time to tackle kernels and learn more about them.

In a recent job interview I was asked how I might resolve issues that manifest as a blinking cursor at the top of a screen during Linux boot. I have seen this before on personal machines and always chalked the issues up to bad Nvidia graphics drivers, which is a known issue with Linux which is getting better. Once I indicated in the interview that this could be the case, I had feeling from my interviewer that this was one of many, many things that can cause this type of issue. Reminder to self! Kernel knowledge is a weak point of mine I aim to start fixing. Some questions that are worth exploring in this post:

- What is the exact process for a machine to boot in a Linux Environment?

- What components can possibly fail during this process?

- How do we identify the offending process?

- How do we resolve the issue?

-How do we keep it from coming back?

Process for Kernel Loading

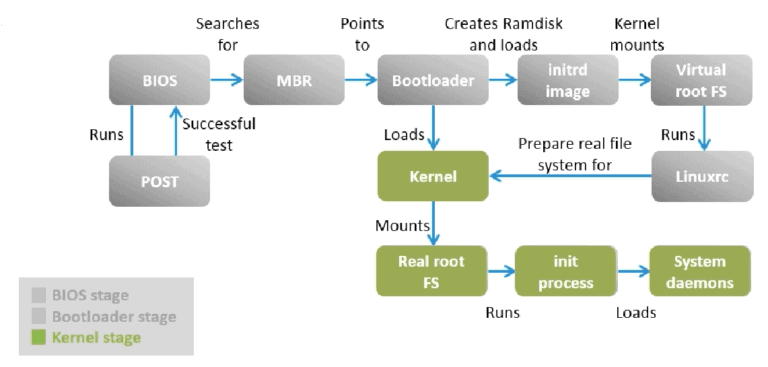

On almost any Linux machine, a typical boot process starts with loading a BIOS (Basic Input Output System). You may have heard this term before, but it essentially runs checks on all hardware to ensure it will be able to operate as expected. From there, the BIOS status is loaded into the MBR (Master Boot Record) which is then loaded in RAM where the remaining steps can be completed.

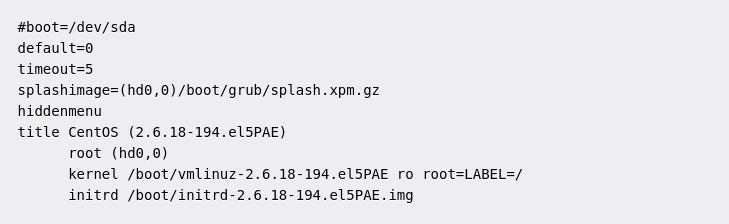

Following a successful BIOS and MBR boot, GRUB is loaded which allows for controlling which OS or Kernel to boot into. By default, the latest kernel version is automatically loaded after a few seconds but other options may be selected if more than one option or kernel is available. GRUB can be controlled just like anything else in Linux by managing the “/boot/grub/grub.conf” or “/etc/grub.conf” files. A typical grub.conf file might look like the following:

The first process that loads for any kernel is “/sbin/init” which always has a process ID of “1” - makes sense. From there, the initrd is run which essentially reserves a portion of memory (RAM) on the system until the file system is fully loaded. Once the file system is loaded appropriately, a modern tool called “systemd” loads all run levels specified. I won’t go over Run Levels in detail in this post, but the gist is that a Run Level can be anywhere from index 0-6, with index “0” being total shutoff, to index “6” being a reboot. In between those indexes are Run Levels for loading network services, multiple users, graphical interfaces, etc… Hopefully your system makes it to Run Level index “5” at which point a normal login can occur. Run Levels are files themselves and can be adjusted like anything else in Linux, but that depth is a little much for this post - hopefully I can follow-up on those later.

What components can fail during init?

In doing some research on this question, it’s apparent this can become a rabbit hole of many causes so I’ll cover some of the typical ones.

Panics can occur when the kernel image being loaded has errors in it’s source code, such as a typo or corrupted component. Panics can also occur when a driver that should be loaded is improperly loaded or has errors in relation to your other hardware (looking at you Nvidia!). Additionally, any other devices connected to the system can cause a kernel panic such as displays, networking equipment, other hard drives, or really any device. Kernel panics DO NOT indicate that the entire machine is corrupted, but rather that Linux has chosen to stop the boot process to remove the potential for further harm to the system. I like to think of it as making sure you’re oil in a car is changed regularly and is “clean”. You certainly CAN use your car without changing it’s oil, but at some point the system becomes so dirty and corrupted that the entire car stops working. This built in regular maintenance step in Linux is yet another reason they are used for systems that need to be reliable, efficient, and easily workable. However, due to there being such an exhaustive list of possible causes for a panic, it’s necessary for a Linux machine to have an “easy” identifier for what is causing the panic - finding that identifier is discussed below.

How do we identify the offending process & remove it?

This is where the process can get a little tricky in terms of finding the issue. Hopefully the reason for a kernel panic is listed on the GRUB boot loader screen which can might typical issues easy to find (just read the info on GRUB and Google or hopefully recognize the issue and resolve. Where things start to get complicated are more serious issues where the kernel cannot access the logs on your Hard Drive. This is a security mechanism to ensure your data is not overwritten by corrupted information. The downside to this is it results in logs not being stored at all. The fix for this is to add a redirect to the swap partition for all logs. This makes sure logs are captured and can be read once an older version of the kernel is loaded or otherwise repaired.

How do prevent the issue from reoccurring?

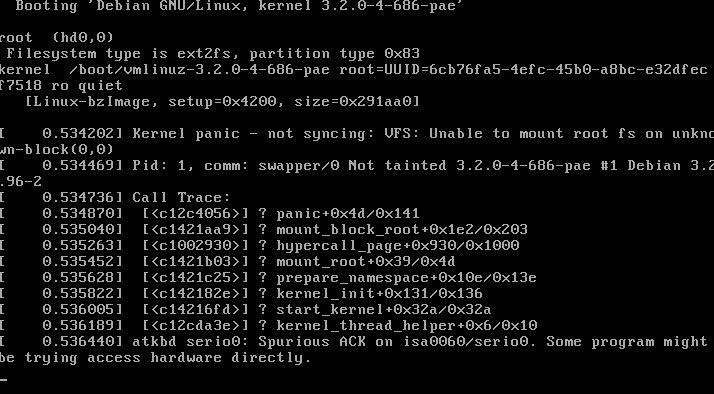

Repairing the issue (assuming it is more complex than a quick kernel image redirect to storage) involves reading the logs which have been redirected to swap space. An example of such a situation might the following:

Let’s say the kernel version was updated and now weird issues are happening that prevent booting to the kernel or otherwise crashes randomly even if the kernel boots fine. To resolve such an issue, we can use our terminal to remove old versions of the kernel and even install new ones! This is one of the major features of a linux file system and how they boot. How many times have you tried to “Repair” a disk or file system on Windows or Mac only for their to be a cryptic message of failure or “unable to repair disk”. At that point most users remove their data and reinstall the OS from scratch….so tedious and unnecessary!

To remove old versions of the kernel we can run the following:

sudo apt remove "oldkernelversionhere"

sudo apt install "newkernelversion"

sudo rebootNow that was easy! Of course verifying the kernel versions can be somewhat difficult initially but once you get the hang of a kernel image file name, it quickly becomes easily identifiable. A version might look like the following:

linux-image-4.8.0-44-genericAt this point you can only prevent the issue from reoccurring by making sure the kernel version does not update to whatever version caused the crash. This can be easily done by verifying the offending version and entering it in this command:

sudo apt-mark hold "packagename"That’s about all you can do until the specific bug is hopefully fixed by the community. Diving any further than this to fix the bug is certainly out of my scope of knowledge but I hope I can learn enough to know where the specific bug exists as I learn more about Linux.

To recap, a typical kernel loading process includes:

Loading the BIOS > Sending to MBR > MBR loads initrd into memory > initrd mounts the hard disk and grabs kernel image > run levels begin loading.

It’s apparent that the control over each process of the boot cycle is a strength of Linux machine and in large part is what makes them so reliable. Being able to revert easily to old versions of the kernel as well as making adjustments to how each component in the boot process loads and what it loads allows for granular control that simply doesn’t exist on other OS’s. I can’t recall how many times I have had a Windows Update brick my machine and cause a Blue Screen of Death only to have that same Operating System be unable to revert back, leading to the only viable solution being a reloading of the OS entirely with a wiped Hard Drive. It’s clearly worth the effort to understand how these machines initialize so you can have granular control and resolve issues without needing the Microsoft or Apple gods (or daemons?) on your side.